Marking the “beginning of the end”, 25 years ago Britain’s Union Jack flag was lowered at the Government House in Central Hong Kong for the final time, replaced with the yellow and red of the Chinese Communist regime in Beijing.

While British Hong Kong once served as a place of refuge for those fleeing communism and repression of mainland China, today, many of the pro-democracy campaigners, who rose to prominence in the Umbrella movement of 2014-15 and the protests against the imposition of Beijing’s so-called national security law in 2019-20 have either fled the city or are in jail.

One such activist, Finn Lau, the founder of Stand with Hong Kong and Hong Kong Liberty, who fled his hometown to the UK after being arrested for participating in a protest on New Year’s Day in 2020, told Breitbart London that the Hong Kong Handover was one of the “biggest mistakes of the century”.

“It handed over millions of people to a dictatorship and marked the beginning of the end,” Lau said. “It is also one of the tragic legacy of Henry Kissinger, former US Secretary of State, who underpinned the so-called ‘Engagement Policy‘ to appease the Chinese Communist Party since 1970s. Without his overwhelming influence upon Thatcher on Hong Kong issues in the early 1980s, the world would be different now,” Lau claimed.

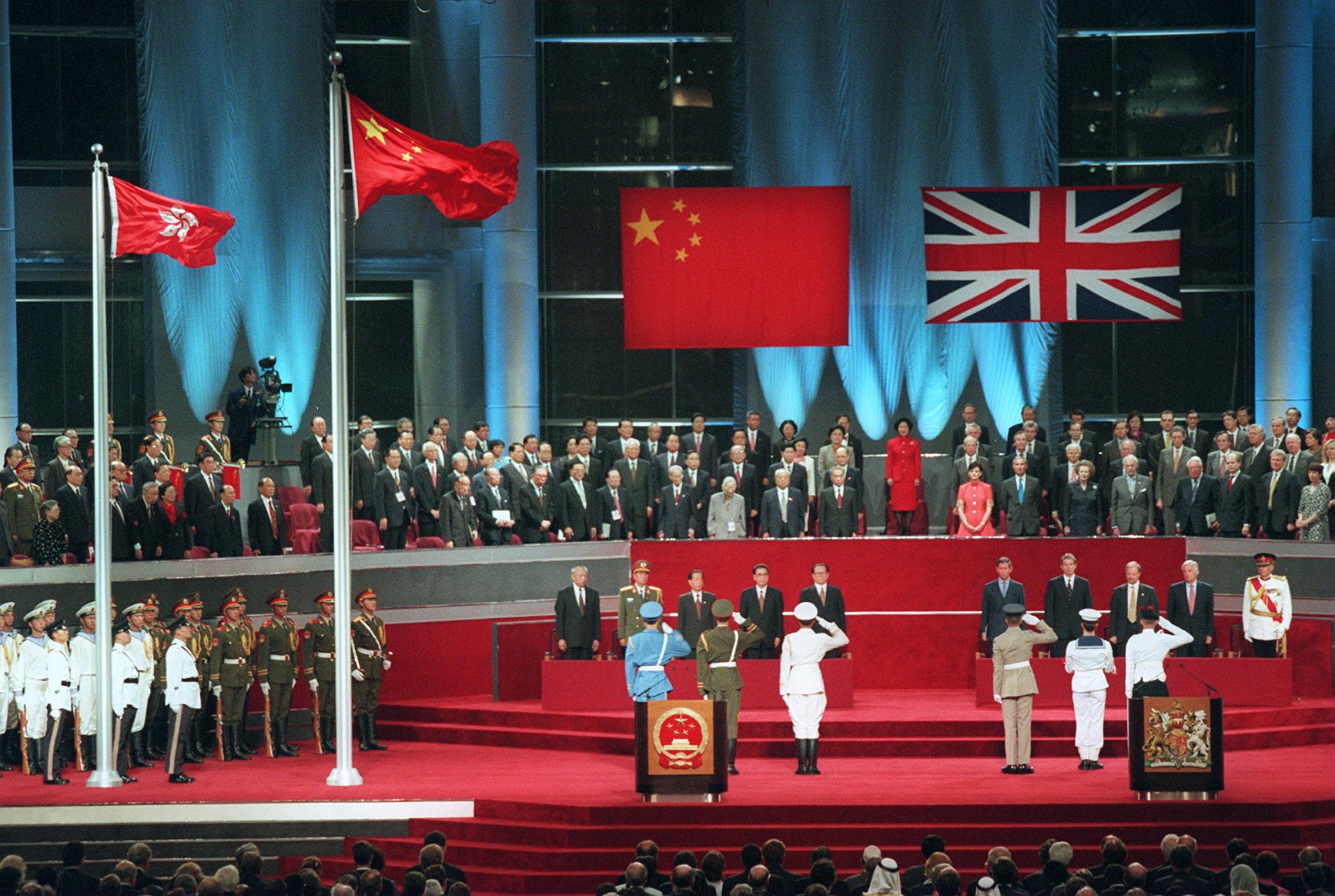

Dignitaries including Jiang Zemin, Li Peng, Tung Chee-Hwa, Prince Charles, Tony Blair, Robin Cook and Chris Patten, receive a salute at the Hong Kong handover ceremony, to mark Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty at midnight, 30 June 1997, Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre,. (Photo by Robert Ng/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

This year, on the 25th anniversary of the Handover, the grim reality of the state of freedom in the city was shown as foreign journalists were barred from entering the territory and the only scheduled protest was cancelled after police threatened to use the powers granted under the national security law to arrest activists for supposed ‘sedition’. Demonstrating that Hong Kong is now fully under the boot of Beijing, Chinese dictator Xi Jinping travelled to the city, his first official trip outside of mainland China since the outbreak of the Wuhan virus.

“A brighter future will beckon, if we forge ahead with perseverance,” Xi said while parading his power at the West Kowloon Train Station, the site where former British consulate employee Simon Cheng was kidnapped and brought to a black site prison in the mainland where he was tortured and interrogated for days by communist apparatchiks in 2019 for his alleged contacts with the pro-democracy protests.

The show of force by Xi Jinping demonstrates the contempt held by the communist leader for the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, which promised that Hong Kong would maintain its freedom from the socialist system for 50 years after the Handover in 1997.

From a Rock Into a Pearl

The British Empire took control of the island of Hong Kong under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking following the defeat of the Qing Dynasty during the so-called Opium Wars. Britain’s territorial holdings in the region would expand to the Kowloon Peninsula in 1860 and later to the New Territories in 1898 when the United Kingdom leased the area from the imperial government in China for 99 years.

With the Crown being predominantly preoccupied with its colony in India and Shanghai emerging as the preeminent port of trade for China, Hong Kong appeared set to become just another minor trading hub in the British Empire’s overseas properties.

Bereft of any natural resources aside from its harbour, the island’s prospects were largely discounted by figures such as then-foreign secretary Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, who declared that it was a “a barren island, which will never be a mart of trade.”

The pessimistic assessment was seconded by Colonial Treasurer of Hong Kong, Robert Montgomery Martin, who said in 1844: “There does not appear the slightest probability that, under any circumstances, Hong Kong will ever become a place of trade.”

Despite the dour outlook, with the implementation of British principles of liberty, such as property rights, contract law, freedom of speech, and the establishment of a judiciary based on common-law principles, the island began attracting migration throughout the region and slowly emerged as a trading hub.

1860: A sailing ship in Victoria harbour, Hong Kong , surrounded by other boats. In the background can be seen in white, and covered with a tarpaulin the old Georgian era battleship HMS Princess Charlotte, a 104 gunner which had become a demasted crew-training ship in Hong Kong Harbour by 1858 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

However, the full potential of Hong Kong’s economic might was not fully realised until after World War II. Following four years of brutal repression and economical exploitation from Imperial Japan, which invaded the island on Christmas Day in 1941 and controlled the city until 1945, Hong Kong once again returned to British rule, with Mao Zedong’s communists fearful of sparking a war with an ally of the United States by attempting to seize the territory.

Aside from the fall of Japanese rule, 1945 saw the arrival of perhaps the most significant figure in turning Hong Kong into the “Pearl of the Orient” and a global financial centre, civil servant Sir John James Cowperthwaite.

Born on 25 April 1915 in Edinburgh, Cowperthwaite was heavily influenced by fellow Scotsman Adam Smith, the author of The Wealth of Nations credited as the “father of capitalism”. Posted in Hong Kong as a civil servant in the Department of Supplies, Trade and Industry in 1945, Cowperthwaite noticed that despite lack of government spending, the city’s economy was rebounding on its own naturally once freed of the constraints imposed by the Japanese.

This led to him developing the laissez-faire economic theory of non-interventionism that he would later institute as Financial Secretary of Hong Kong from 1961 to 1971.

Hong Kong representatives John James Cowperthwaite, left, and C. Y. Kwan are at a meeting of the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East in a Tokyo Hotel on April 3, 1967. (AP Photo)

Explaining his philosophy in 1966, he said: “In the long run, the aggregate of the decisions of individual businessmen, exercising individual judgment in a free economy, even if often mistaken, is likely to do less harm than the centralised decisions of a government; and certainly the harm is likely to be counteracted faster.”

Coupled with strong rule of law protections, Cowperthwaite’s low tax, low spending regime and his refusal to use government resources to bail out failing firms ushered in an era of almost unparalleled economic growth, seeing the once “barren” rock of an island eventually experience a higher GDP per capita than in Great Britain.

During Cowperthwaite’s tenure as Financial Secretary in Hong Kong, real wages rose by 50 percent while the percentage of those in acute poverty fell from 50 to 15 percent, according to analysis from University of Alabama Professor Andrew P. Morriss.

Despite affording the city with a high degree of personal liberties and economic freedoms, democratic reforms were still lacking. Hong Kong Liberty founder Finn Lau told Breitbart London: “The UK had introduced democratic reforms and provided its colonies with the right of self-determination after the Second World War. Yet, Hong Kong was the exception.

“Whilst British governors like Sir Mark Young attempted to carry out democratic reforms such as the Young Plan in Hong Kong, the leaders of Chinese Communist Party repeatedly threatened the UK government with military consequences had they introduced democracy and self-governance to Hong Kong. In essence, it was Beijing that dwarfed Hong Kong’s democracy.”

The Iron Lady and the Red Dragon

Though the 99 year lease secured under the Second Convention of Peking 1898 only applied to the New Territories, following the admittance of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) into the United Nations in 1971, the communist government in Beijing began using the socialist legal theory that all of the UK’s holdings in the region were signed during a power imbalance between Imperial China and British Empire and therefore were illegitimate and should be returned to China.

While the communist legal theory has never been recognised by any international body and the fact that the treaties were signed with the Qing Dynasty, not the PRC, with the diminished status of Britain’s global reach in the wake of the Second World War and the Suez Canal Crisis, Beijing began flexing its muscles.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was dubbed the ‘Iron Lady’ by a Soviet journalist for her tough and uncompromising leadership style, was faced with a horrifying prospect, namely, the invasion of Hong Kong by the Red Army. Although paramount leader Deng Xiaoping was seen as a liberaliser when compared to his fanatical and murderous predecessor Mao Zedong, the ageing leader took to threats to ensure that Hong Kong would come under communist rule.

During negotiations with Thatcher in 1982, Xiaoping is reported as telling the British PM: “I could walk in and take the whole lot this afternoon.”

Recognising the shift in power, Thatcher admitted: “There is nothing I could do to stop you… but the eyes of the world would now know what China is like.”

Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party Central Advisory Committee, Deng Xiaoping (L) and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (R) talk in a file photo dated 24 September 1982 at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing during one of their meetings leading up to the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the future of Hong Kong on 26 September in 1984, setting up the territory as a Special Administrative Region of China. . CHINA OUT / AFP / XINHUA / STR (Photo credit should read STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Rather than risking a conflict with the CCP, Tatcher negotiated the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, which guaranteed that Hong Kong would retain domestic independence from Beijing for fifty years after the Hong Kong Handover in 1997 under the banner of “One Country, Two Systems”.

In an ominous instance of foreshadowing the communist’s unwillingness to actually liberalise or indeed allow Hong Kong to maintain its freedoms, the chief Chinese signatory of the agreement, Premier Zhao Ziyang was stripped of all of his rank and stature within the CCP and placed under house arrest for the rest of his life following his support of the 1989 pro-liberty protests in Tiananmen Square, where Deng Xiaoping’s supposedly liberal government massacred thousands of people.

Nevertheless, the transfer of power was not called off and on July 1st, 1997 the city of Hong Kong was officially put under the rule of Beijing.

Chris Patten (R), the 28th and last governor of colonial Hong Kong, receives the Union Jack flag after it was lowered for the last time at Government House – the governor’s official residence – during a farewell ceremony in Hong Kong on June 30, 1997, just hours prior to the territory’s handover from British to Chinese rule. (Photo by EMMANUEL DUNAND / AFP) (Photo by EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images)

“I do not think the UK had a choice about handing Hong Kong to China, but certainly the UK should have done more at an earlier stage to embed democracy in Hong Kong and to safeguard Hong Kong’s freedoms, and the UK should have been more robust much earlier when the signs of the erosion of Hong Kong’s liberties first became apparent,” Hong Kong Watch founder and chairman Benedict Rogers told Breitbart London.

“More should have also been done to establish a mechanism of recourse and enforcement in the event of violations of the Joint Declaration. While the UK has been very generous in providing a lifeline for Hong Kongers to leave the city and find a new future in the UK, it has done nothing to hold Beijing to account for violating an international treaty.”

Be Like Water

One year after the death of Margaret Thatcher and just two years into the reign of Chinese dictator Xi Jinping the first signs of the erosion of Hong Kong liberties began in earnest. At the behest of the communist regime, the CCP-aligned puppet government of Chief Executive CY Leung attempted to institute so-called “Moral and National Education” which would have overturned over a century of British-style education in the city in favour of pro-Beijing communist propaganda.

At the same time, the local government also was seeking to implement the demand from the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China(NPCSC) for Beijing to have the authority to select the candidates for the election of the chief executive of Hong Kong.

The reforms, which were seen as blatant violations of the “One Country, Two System” guarantee of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, sparked what has become known as the Umbrella Movement, when hundreds of thousands of students and citizens occupied Central in protest for 79 days, using umbrellas to shield themselves from the repeated barrages of tear gas fired by the police.

The Umbrella Movement was successful in blocking the education reforms for a time, however, the move to allow Beijing to handpick candidates for the local elections went ahead. Yet, it also came with the elevation of youth activists such as Joshua Wong, Agnes Chow, and Nathan Law as key figures in the fight for freedom.

HONG KONG – SEPTEMBER 28: Protesters clash with riot police on September 27, 2014 in Hong Kong. Thousands of people kicked off Occupy Central by taking over Connaught Road, one of the major highway in Hong Kong, in protest against Beijing’s conservative framework for political reform. (Photo by Anthony Kwan/Getty Images)

With notoriety and fame came danger, however, with Wong being imprisoned in 2017 for his role in the Occupy Central protests. Both Wong and Chow would later be imprisoned for joining the 2019 pro-democracy protests, and Nathan Law was forced into exile, seeking refuge in London.

The targeting of the central leadership of the Umbrella Movement prompted later activist groups to opt for a more decentralised structure. Adopting the phrase of famed Hong Kong martial artist Bruce Lee, demonstrators were called on to “be like water,” with the protests against the proposed extradition bill in 2019 becoming a network of leaderless cells organised on encrypted messaging apps like Telegram..

The Hong Kong government ultimately backed down on the extradition bill, yet, in response to the millions of citizens protesting in defiance of Beijing authority, a so-called national security law was illegally imposed on the city in 2020, criminalising engaging in “foreign interference”, “secession”, “terrorism”, and “subversion of state power”.

Though clearly a violation of the freedoms promised under the Sino-British Joint Declaration, to date, the British government has done little more than issue sternly worded statements of condemnation. This week, a group of MPs have called on the government to impose sanctions on Hong Kong leadership and CCP officials involved in the repression, yet, it remains to be seen if Prime Minister Boris Johnson — a self-described ‘Sinophile’ and proponent of a post-Brexit trade deal with Beijing — will take such action in defence of Hong Kong.

HONG KONG, HONG KONG – JUNE 12: A protester makes a gesture during a protest on June 12, 2019 in Hong Kong China. Large crowds of protesters gathered in central Hong Kong as the city braced for another mass rally in a show of strength against the government over a divisive plan to allow extraditions to China. (Photo by Anthony Kwan/Getty Images)

The introduction of the national security law, coupled with the imprisonment or exile of most prominent pro-democracy activists, the heavy-handed and often brutal tactics of the Hong Kong police and draconian coronavirus regulations has seen protests all but disappear from Hong Kong.

Time will tell, however, if the flame of freedom first brought to the once barren rock by British imperialists still burns on within the hearts of the Hong Kong people.

As Joshua Wong put it: “Our bodies are held captive, but our pursuit of freedom cannot be contained.”

Follow Kurt Zindulka on Twitter here @KurtZindulka

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.